Fold, Bend, Twist

A typical Yin yoga class likely includes postures such as forward folds, back bends, and spinal twists. In any given Yin yoga session the joints between the navel and the knees are the primary focus, and rather basic shapes are used to stimulate them. The hip joints, sacral joints, and lumbar vertebrae are easily accessed by generally familiar yogic poses, and then held for several minutes. Healthful benefits ensue.

For instance, we know that stimulating these exact areas results in free and easy movement in sports and the day-to-day. In your mind’s eye, picture how that looks. We also know that these same regions, when stiff and restricted, inhibit normal activity. Life itself becomes difficult, awkward, and uncomfortable. Imagine, now, how that appears.

As the pithy saying goes, “you’re as old as your joints.” Yes, and happily, you’re also as young as your joints. So, Yin yoga, which effectively rejuvenates joints and their surrounding tissues, ensures youthfulness, at any age. All you have to do is to fold, bend, and twist.

A Cornucopia of Possibilities

Hatha yoga postures easily accommodate whole-body muscular ranges of motion, strength, and stamina. There’s truly something for everybody. Every body. After all, didn’t Lord Shiva reference some eight million, four-hundred thousand … or eighty-four thousand … or at least some eighty-four asanas through which to attain yogic perfection? And even as studio classes are usually pared down to include less than half that number, the available repertoire is expansive and comprehensive enough to deliver healthful and potentially enlightening experiences to most everyone.

The Bikram primary series, comprised of about two dozen shapes, offers the same health, fitness, and flexibility results, with an additional perk — heat tolerance. (More important than you might at first think, BTW. We’ll come back to this.) The Hatha Yoga Pradipika references only fifteen, and emphasizes but four, and I can put together an effective Yin yoga class with just three unique shapes.

Surely this isn’t a game of yogasana Name That Tune, but such a distillation process has value. As yoga is a vehicle through which to attain elevated consciousness, and, as it’s said, mastery of just a single posture allows for everything worth knowing to be known, parsimony may be practical. As Antoine de Saint-Exupéry points out, “Perfection is achieved not when there’s nothing left to add, but when there’s nothing left to take away.” Less is more.

But, short of spiritual awakening, whether in service of the posture itself, or of attendant joint actions, in all cases, in a physical practice, just folding, bending, and twisting into various positions is the key. To whatever degree, everyone can do that.

Results Speak Volumes

Historically, yogis of any vintage are a supple, vital, and resilient population group. For instance, a yoga studio owner I know, after being pitched the promises of skeletal adjustment replied, “Chiropractic? Oh, please. I do yoga.” Another yogi, a heralded teacher, described how through his Hatha yoga / meditation practice he beat a well-developed spinal cancer. No small feat. Both yogis move like cats, and neither is a spring chicken — the former was about sixty when she brushed off the spinal cracker.

Interestingly, yogi Paul Grilley mentioned that one of his teachers, martial artist and Taoist yoga master, Paulie Zink, directed him during his training to throw a few punches and kicks, but to concentrate on the yoga. In his own training, Zink worked hard on his skills, related Taoist concepts, and emphasized his yoga and Qigong practice. He moves well.

But these are effectively Yang practices. They’re dynamic. They strengthen and lengthen muscle. But of course, because that’s exercise, right? Well it’s partly right.

My first Yin yoga teacher, Denise Kaufman, says, “athletes don’t retire because their muscles give out, but because their joints do.” Fair enough, but don’t these other forms of yoga address joints? No, not so much.

Muscles, when contracted — as in while “activating” a Hatha pose —, are protective of joints. The joints involved are secured by criss-crossing tensional forces, and those forces are absorbed by the active muscles themselves. And, that’s well & good during Yang endeavors. Yin yoga, on the other hand, due to its characteristic “slow, deep stretch,” encourages muscles to relax, which then provides access to surrounding fascia, ligaments, the joint capsules, and effectively the bones, too, ultimately stressing the joints themselves. Stress, by the way, when applied judiciously, stokes the organism into what Hans Selye called super-compensation.

What Doesn’t Kill You

Selye, a Hungarian medical researcher — known for his various experiments with lab rats which led to the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) —, found that organisms experiencing some sort of (physical) challenge responded in the same way. There was alarm, there was resistance, and, depending on the magnitude of said stress, the subject would either capitulate or rebound as a stronger organism. (Recall the heat tolerance training of Bikram yoga.) This rebound effect, the super-compensation, would become a cornerstone to the training principle, Periodization. Periodization is a progressive, stress management plan for athletes. Oversimplified, it’s: exercise, exercise more, exercise even more / rest / get stronger. Rinse. Repeat. This applies to yoga, too, returning us to the joints and attendant tissues.

The relatively new and novel approach to fitness and yoga, Yin yoga, that emphasizes “exercising” fascia, ligaments, joint capsules, and bone — and not muscle — with stillness has become tremendously popular, not only in Western yoga studios, but in more traditional yogic venues, too. In fact, I was invited to Nirvana Yoga Shala, in Mysore, India to lead a hundred-hour Yin Yoga Teacher Training, which I did, in 2020. The curriculum? Mostly fold, bend, and twist.

Oh, Surely There’s More to It

Indeed. Yin yoga progenitor, and martial arts champion, Paulie Zink will take you down a deep and different rabbit hole. Anatomist, yogi, and short-term student of Paulie Zink, Paul Grilley, has distilled and popularized a portion of Zink’s Taoist yoga that has become Yin yoga proper. His is a mechanical, nuts and bolts approach. Yogi, Bernie Clark, immortalizes Grilley in his Complete Guide to Yin Yoga — The Philosophy and Practice of Yin Yoga. His wordy and worthy tome, well, as Bernie himself says, “is Paul’s book,” meaning that he’s thoroughly documented Grilley’s work. And, my own book, A Righteous Stretch — Yin Yoga: What it is, How to do it, and Why, is a concise take on those elements of Yin yoga I find especially compelling, and how I approach teaching my classes. As well, here’s more on Christopher’s Yin Yoga class structure.

While I consider Paulie Zink and his Taoist slant to be an influence, I am certainly more of the Grilley lineage, and adhere to a decidedly Western approach, (owing to my decades of professional fitness coaching). Even so, even as “yoga” has percolated through society at large, the idea of training fascia, stillness as exercise, and a discreet practice called Yin yoga, is still on the fringe.

Nonetheless, the joints of the hips, sacrum, and low back respond favorably to regular stress — in fact, as part of living organisms, they require such stress to remain healthy and functional — and basic Yin yoga postures accommodate admirably.

Though short of eight million, eighty-four, or even twenty-six unique postures, the rather sparse number of shapes best suited to a Yin practice are nonetheless sufficient to accommodate pretty much all yogis. That’s because they are all pretty basic positions, and because the posture itself is not the objective. Alignment is unimportant. What’s important is stimulating fascia, ligaments, joint capsules, and the respective joints of the hips and low back, over time. How? By folding, bending, and twisting!

Yin Yoga Postures

The generally accepted Yin yoga catalog of postures seems to be between two and three dozen, including some shapes for the upper body. Yogis are always looking to expand their practices, their experiences, and can be quite creative. My approach to Yin yoga postures is admittedly narrow, maybe even more so than Grilley’s. It should be — potency hinges on purity. In a given month of thrice-weekly classes I’ll use under twenty.

In my repertoire there are twenty-three, including Pentacle — the Savasana analog — Yin yoga postures. I use fewer during individual sessions mainly due to time constraints. An hour-long class only allows for so many long holds, right? Christopher’s Yin Yoga postural duration and variation follows the waxing and waning of the lunar cycle, and nearly each individual shape is represented each month.

Even with lesser inclusion of my least favorites — Frog, Shoelace, and Snail —, the whole of the Yin yoga postural gamut is covered. That’s a good twenty individual shapes, each with its own effect, applied at least once every month. That may not sound like much. That may even sound insufficient. But it’s more than enough when targeting only three joints. Yes, even as the hips are ball-and-socket joints and need stimulation from various directions.

So, here’s a sequence comprised of about a third of all the Yin yoga postures I use. Do the routine a couple times a week and enjoy the benefits.

Eight Yin Yoga Postures

Deep Squat

This is an elementally human shape The Deep Squat should be cultivated in your practice, and used in the day-to-day.

Set your feet some comfortable distance apart. You’ll know the width is correct when you can most easily relax into this shape, without having to use your muscles to hold the position. An exception is, depending on ankle dorsi-flexion limits, when the anterior tibialis muscles fire to keep you from falling backwards.

Feel free to add that Yang element, that muscular effort, if you want. Or, slip a folded blanket beneath your heels to tip you forward enough so that you can fall into the shape. In either case, you want to reach full dorsi-flexion, that is, compression in the front of the ankle joint. Also, use a block or bolster beneath the hips, as needed, to reduce the load on the knees.

Reach your hands out to find purchase on the mat, or floor. Let your elbows bend. And, let your chin fall toward your chest.

Use your Yin breath.

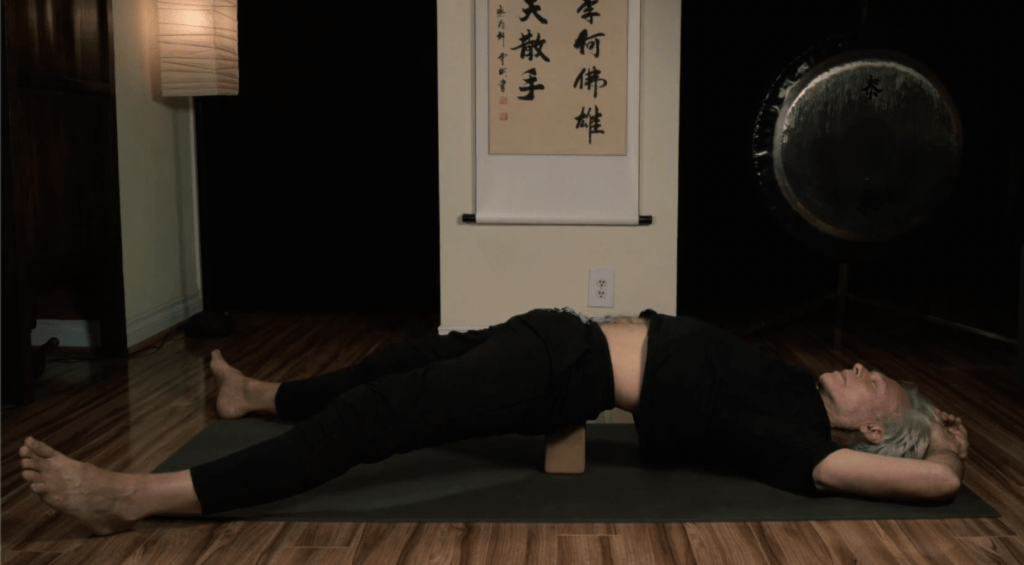

Supported Back Extension

An easy, effective and especially Yin posture. Use it as an alternative to Saddle if strong knee and ankle flexion is to be avoided.

Take your yoga block, and lie supine. Bend the knees so the feet come flat to the mat, and raise the hips. Choose the low, medium, or high side of the block and place it beneath the hips. Make sure the top edge of the block is no higher than the top edge of the pelvis. That means that it’s not under the spine. Stretch out the legs, let the thighs roll out to either side. Brings hands and arms by the sides, or reach them overhead.

Breathe your Yin breath.

Caterpillar

This most basic posture provides insight into what sort of hip and back flexibility you actually have. Notice whether the limiter you’re experiencing is tensile or compressive, and if compressive, how and where.

Sit with legs outstretched to your front. Fold forward to whatever degree. Add some Yang by drawing the toes and tops of feet back toward shins, actively extend the knees, flex the hips, round the back, and tuck the chin to effect reciprocal inhibition, and to stimulate the Superficial Back Line.

Reciprocal inhibition is the cooperative response of the body where when muscles on one side of a joint are contracted the muscles on the opposite side relax. This can noticeably deepen the posture right away.

The Superficial Back Line, described in Tom Meyers’, Anatomy Trains, is a myo-fascial continuity — a passive line of tension running from the undersides of the toes all they way to the base of the skull, and over the head to the brow line — that allows for quite literally stretching, all-at-once, from head to toe!

Continue with your Yin breathing.

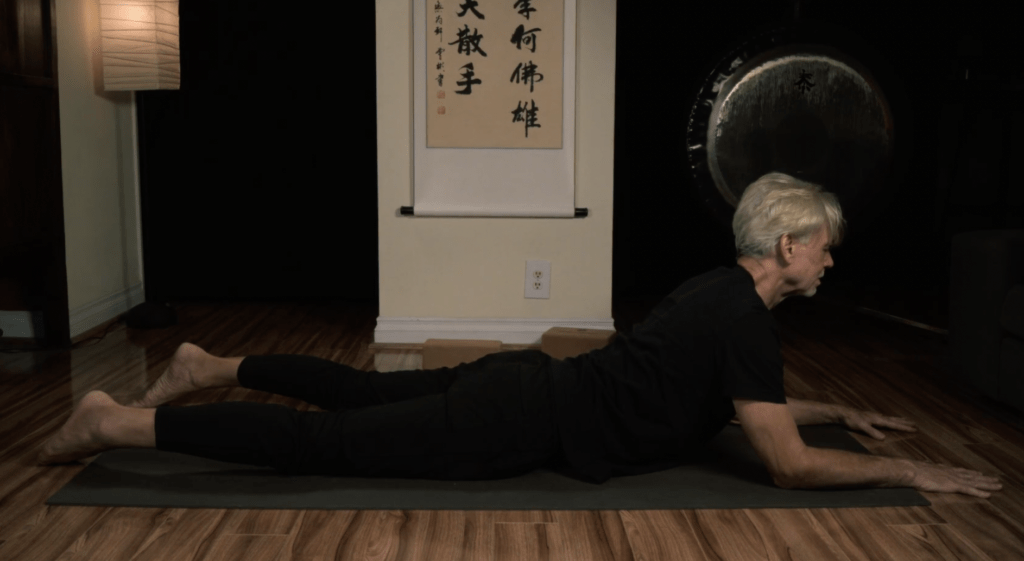

Sphinx

Simple, easy, effective. Perfectly Yin.

From a prone position, raise the upper body onto the elbows. Make sure the elbows are placed just in front of the shoulders (and not behind) so you are effectively propped up, and not actively holding yourself in position. Let the heels fall out to either side. Look straight ahead, or up, if you have the range of motion in the neck.

For some the lumbar vertebrae will reach compression right away, and their back bend won’t be very deep at all. (Like mine.) Others will find that bony limitation much later, and may also be able to tilt their head back far enough to look at the ceiling. Remember, the bony limitation is a hard boundary. It’s less common, but possible for abdominal tension to be a limiter.

Carry on with your Yin breathing

Butterfly

An asana from the Pradipika!

From a seated position, bring the soles of the feet together some comfortable distance in front of you. Let the knees fall out to either side. Fold forward.

This shape reaches into the inner thighs, and the hip joints. Something to notice is whether the limiter is inner thigh tension, or some restriction specifically in the joints themselves. Here, I feel very little tension in the inner thighs, and quite a bit of compressive discomfort in the back of my hip joints. That’s bone-to-bone compression, and a hard boundary. In this position my posture is functionally complete even as it appears to be just getting started — “knowledge is good.”

Stay with your Yin breathing.

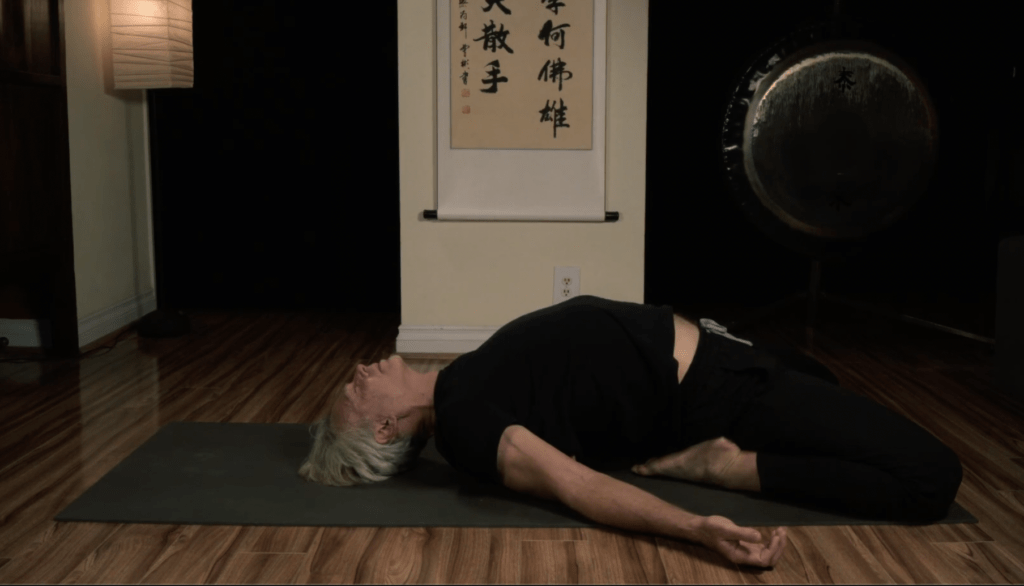

Saddle

Sit on your heels, spread your knees about as wide as the narrow end of your mat, and lie back. Come out by just sitting up, gradually leveraging yourself up using your elbows, or by rolling off to one side. It’s hard to be graceful here.

The Hatha version of this shape is suptaVAJRasana, not suptaVIRasana. In the former you’re sitting on your heels and effecting a back bend and hip extension. The latter, where the shins are placed outside of the hips and thighs, removes the hip extension, and the back extension from the posture. It does introduce internal rotation of the hips, and tibial torsion (at the knees), which is well and good, if that’s your aim. It’s just not a back bend.

Even if at first this feels impossible, since there isn’t a compressive limiter to overcome, it’s just a matter of time before you can “complete” the pose. Use however many bolsters or blocks you need to accomplish the shape, and removing them one at a time as range increases. Really. I’ve had students who had to start with three or four bolsters, but reduced that to one within a month or two. Since the knees and ankles are very strongly flexed here, some might opt to use a Supported Back Extension as a substitute.

Now to increase both back and hip intensity, place a block or two beneath the hips.

Maintain your Yin breathing.

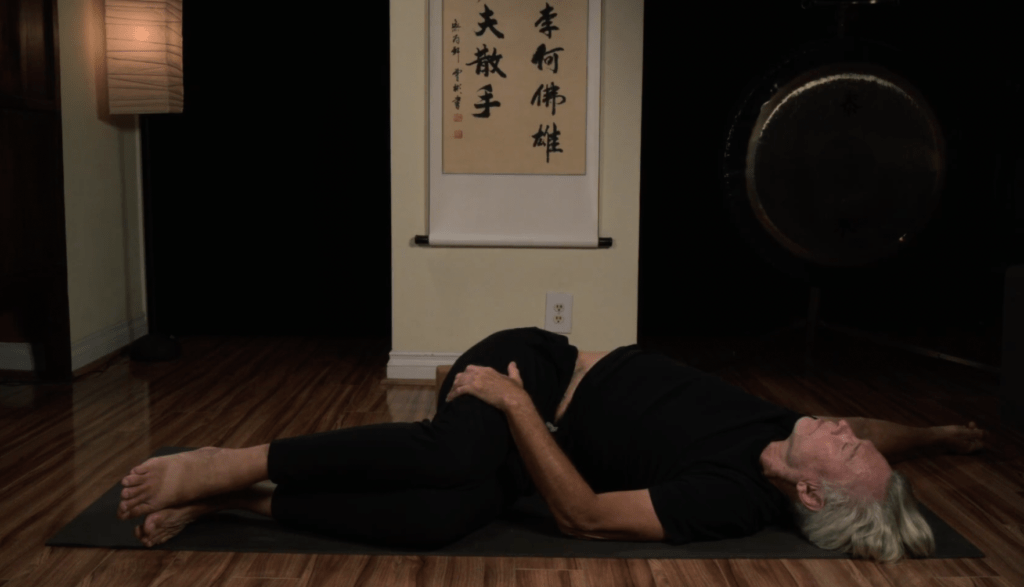

Twisted Root R & L

Unless you’re a gymnast, a dancer, a surfer, a yogi, or such, regular spinal twisting is not likely to be part of the day-to-day. But, even if, protracted twisting is pretty much ignored — unless you’re a Yin yogi. Our primate cousins, Chimpanzees, don’t twist out of “design.” Old folks, generally don’t twist out of disuse, and they devolve physically. Western nostrums, and chiropractic haven’t solved the problem. I wonder what could …

Lie on your side, flex your hips, and knees — as pictured — stacking the hips, knees, and ankles vertically. Take the top arm out to the side, on a diagonal, above the shoulder. Tissues across the front of the body will lengthen, not just those deeper tissues around the spine. After a few minutes, if it’s not there already, the top arm could be close to touching the floor. Your range can vary session to session, so long term progress might not seem linear.

Should you be particularly limber, instead of just stacking the hips, tilt them forward. First, reach the bottom leg out lengthwise along the mat, and lower the top knee to the floor. That starts the twist right away. Should more twist be needed, slide that top knee forward six or eight inches.

Hang in with your Yin breathing.

Pentacle

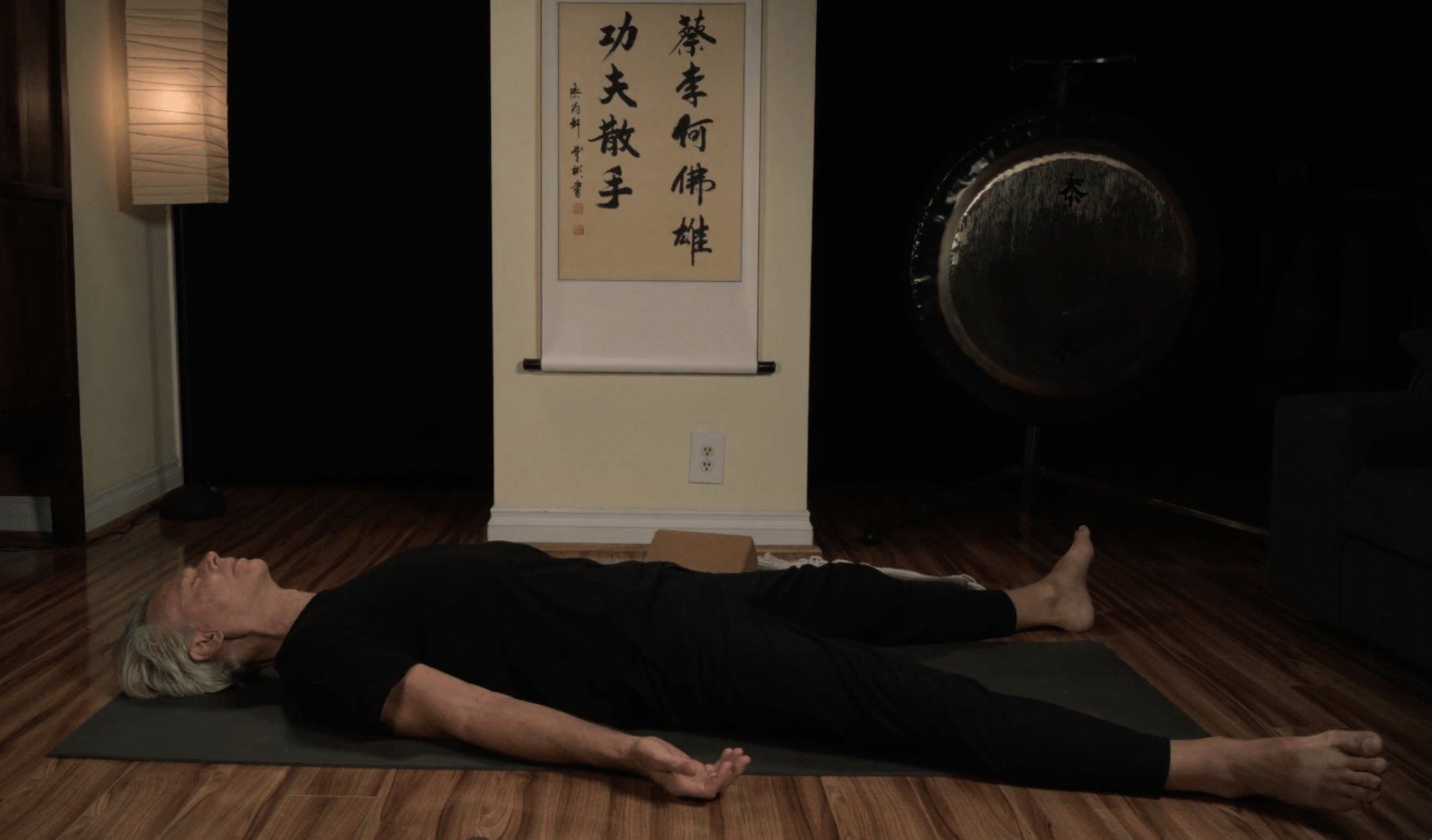

This is Yin yoga’s Savasana, or corpse pose. Lie supine. Adjust clothing, and position to find comfort and symmetry on the mat. Spread feet apart, and let thighs roll out to either side. Bring hands and arms you to either side, palms up. Readjust if needed. Breathe normally. Relax fully.

If you haven’t already, join me for a live-streaming Yin yoga class on Zoom. Or, take classes anytime, On Demand. If nothing else, why not try out a FREE WEEK of Yin yoga?